A growing body of evidence suggests that having a well-defined eating window plays an important role in maintaining health. However, this is not to say that avoiding eating (“starvation”) is recommended-as calories should not be decreased.

What scientists are saying is that it’s time to eat less. What they mean, however, is not a reduction in calories – but a reconsideration of when food is eaten. A growing body of evidence suggests that “24-hour” eating can be bad for your health.

A study published in 2021 found that limiting the food window to a period of 10 hours had a positive effect on health parameters – compared to a 12-hour period and with equal caloric intake. In the article below, we explore why this is the case.

The food window – what is it?

The term “feeding window” (literally, “feeding window” ) originated in the theory of interval fasting, an eating regimen that involves eating during a strictly limited period of the day. The classic pattern is 16 hours of fasting and 8 hours when food is allowed.

The first study of interval fasting dates back to 2012 – and over the past decade, many experiments have been conducted confirming a number of health benefits. In addition, recommendations for the length of periods have been adjusted.

Importantly, the current scientific literature is increasingly replacing the term “interval fasting” with “food window” – as being more calorie-neutral. Obviously, the word “fasting” is often associated with the need to cut calories – which is erroneous.

Current Statistics

Statistics² show that the length of the food window for most people is more than 12 hours – and for 50% of the population, more than 15 hours. Considering the 3-4 hours the body needs to digest food, we are talking about almost 24-hour digestion.

Scientists have neatly hypothesized that such eating patterns may be the cause of epidemics of obesity and diabetes – but there is currently no definitive data to support or refute this view.

Biorhythms and nutrition.

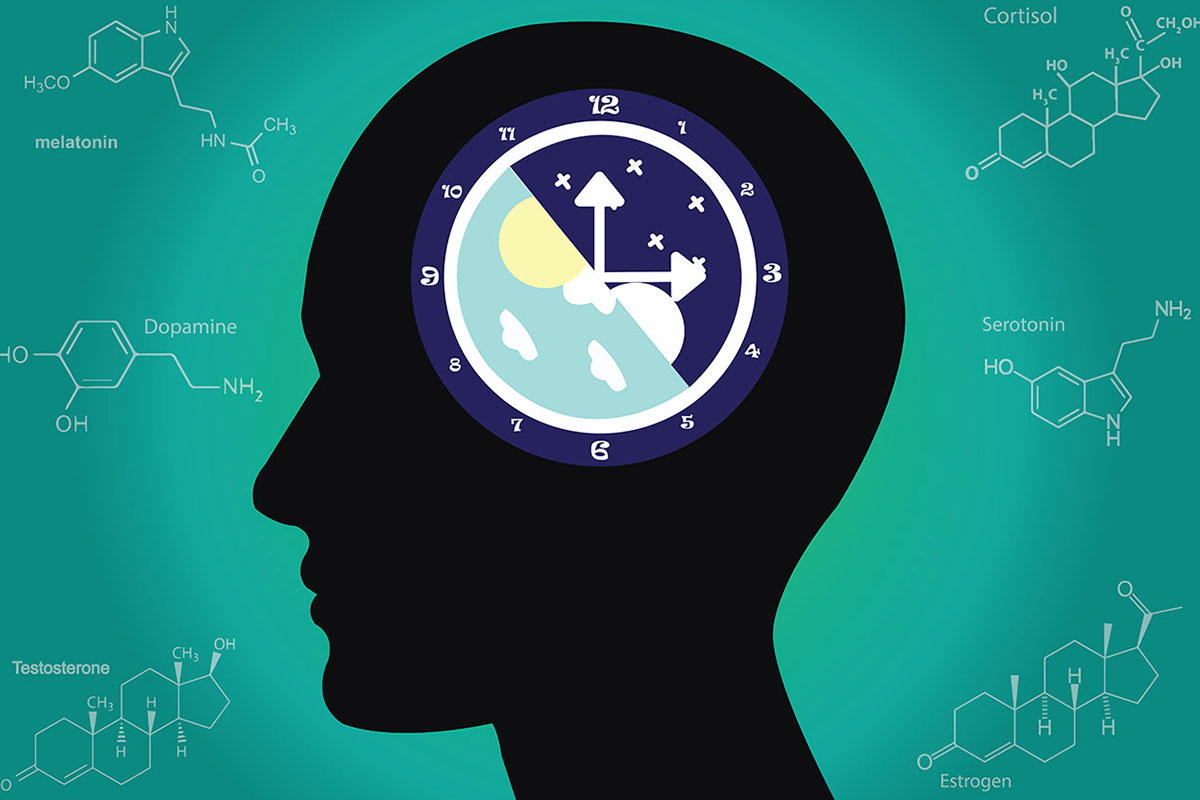

The workings of human metabolism are characterized by a 24-hour cycle related to the level of natural light. In fact, the production of many hormones is tied to a certain time – through which the body regulates both metabolic processes and food intake.

In particular, during daylight hours, the body² is in “wakefulness” mode (the pancreas produces insulin to digest carbohydrates and provide energy to the muscles) – whereas these processes are significantly restricted during dark hours of the day.

What was it like before?

Probably before the invention of electricity 150 years ago, people very rarely ate food at night and in the late afternoon and evening – that is, the length of the active metabolic period was strictly limited by the length of the daylight hours.

In addition, food was most likely eaten periodically as it was found – and there was no free access to high-calorie food. Not to mention that natural foods were fundamentally different from the ultra-processed foods available in supermarkets today.

How to eat to stay healthy?

Once again, let us emphasize that the emphasis of the phrase “the benefits of fasting” in the understanding of most people is reduced to the need to fast – whereas the recommendations speak not at all about restricting calories, but about the benefits of having a certain and repeatable schedule of food intake.

That is, what is meant is not refusal to eat (“starvation”) – but control over the times when food is consumed (“food window”). Importantly, it’s not about cutting calories or pushing oneself into a state of acute hunger.

Experts believe³ that eating at random times is one of the key causes of health problems such as impaired glucose sensitivity, elevated blood pressure, increased “bad” cholesterol – and, ultimately, overweight gain.

Nutritional Window – Recommendations.

The 2021 study¹ mentioned at the beginning of this material compared eating patterns with a 10-hour and a 12-hour food window – meaning, respectively, a 14-hour and 12-hour dietary restriction (“starvation”). A total of 78 people participated in the study.

After 8 weeks of the experiment, the group adhering to the 10-hour food window showed not only a decrease in body weight (minus 8.5%), but also a decrease in fasting glucose values. The caloric content of the diet and the level of physical activity were identical in relation to the group with the 12-hour food window.

There is a growing body of evidence that having a clearly repeated period of food intake (the “food window”) plays an important role in maintaining health. However, this is not to say that avoiding food (“starvation”) is recommended – because calories should not be reduced.

Consult a specialist for specific contraindications.

Data sources:

- Effect of time restricted eating on body weight and fasting glucose in participants with obesity: results of a randomized, controlled, virtual clinical trial, Source

- The when of eating: The science behind intermittent fasting, source

- Clinical study finds eating within a 10-hour window may help stave off diabetes, heart disease, Source

The articles on this site are for information purposes only. The site administrators are not responsible for attempting to apply any recipe, advice or diet, nor do they guarantee that the information provided will help or harm you personally. Be cautious and always consult a doctor or nutritionist!

*All products recommended are selected by our editorial team. Some of our articles include affiliate links. If you buy something through one of these links, you help us earn a small commission from the seller and thus support the writing of useful and quality articles.